The How to be a Curious Entomologist workshops were set up to teach people how to make an insect collection — simply, with easy, cheap, often home-made equipment. But why, in this day and age of electronic wizardly, high-spec digital cameras, email and internet should you need a collection? Because only about 5% of UK insect species can be definitively identified from a photo. Large moths, butterflies, dragonflies, grasshoppers and a few others are unmistakable. But that leaves 95% which can only be firmly named by looking at obscure characters under a microscope — often individual bristles on individual legs.

I recently undertook a reconnaissance survey visit to a small local nature reserve. It was late in the season, but I was told there were quite a few invertebrate records on file, collected over several years of casual observation. These would, no doubt, be useful. What I got was a list of common garden butterflies and bumblebees. The reserve warden was slightly disappointed when I all but dismissed them as useless. The trouble is they were all obvious common species that could be found in almost any garden in London. They gave no insight into the special habitat or distinct insect community of the site. If I had only been handed a scruffy box full of badly pinned and awkwardly carded insect specimens, oh how different it would have been.

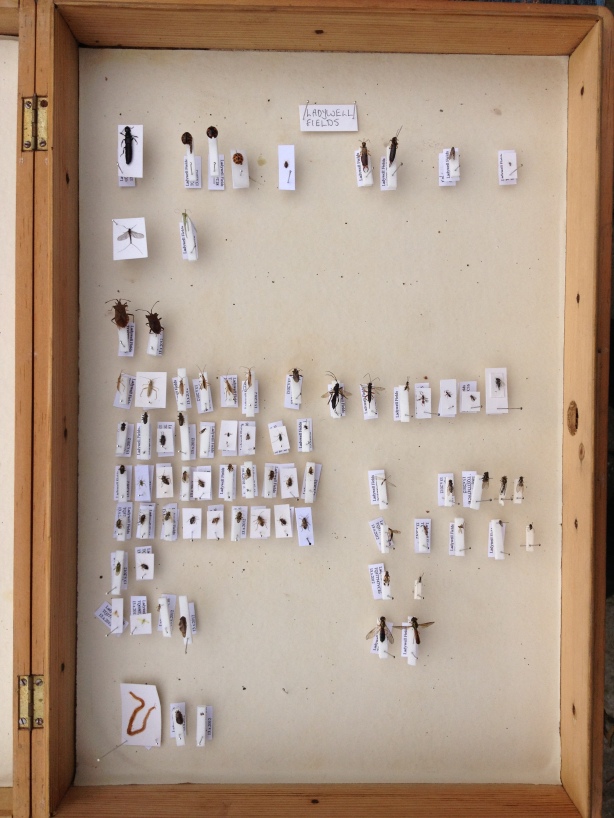

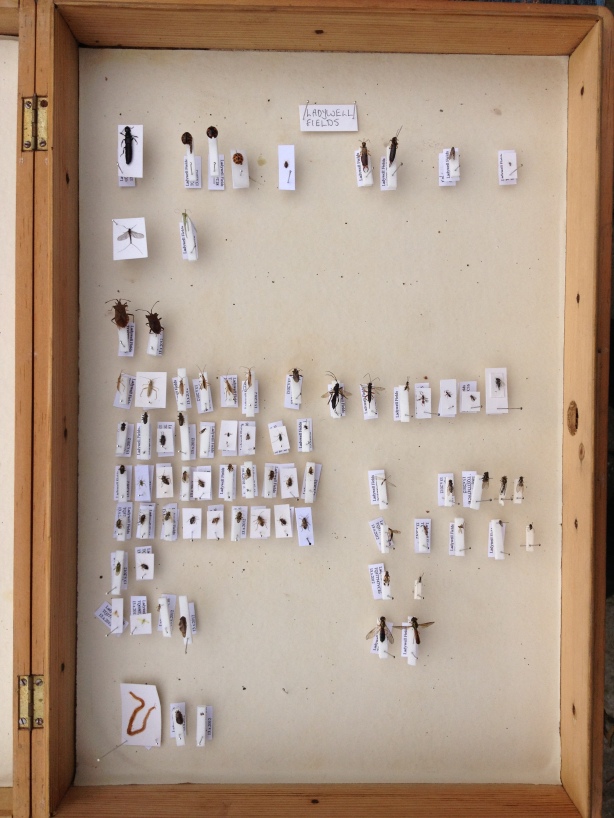

Late-in-the-season finds from Ladywell Fields.

After three curious workshops, we now have three prospective insect collections. They can be added to, piecemeal, over many years if need be. But whenever it comes to finding out what occurs on one of these sites, at least the incoming surveyor will have a starting point. And I know there are some gems in there.

The identifying bit of entomology is often what takes the time, and I just don’t have the time to work thoroughly through all of the collections we made, but here, at least, is a taster of some of the more unusual things that turned up.

Brachycarinus tigrinus Schiller, a small pale speckled ground bug (family Rhopalidae). This distinctive bug is a recent colonist to Britain, and was first found here in 2003, in Battersea Park, central London (by some chap called Jones, apparently). It has since been found in several brownfield localities in Essex and London, but is still very rare and confined to a narrow belt of localities in the Thames Gateway. It was almost the very first insect collected at the Deptford Creekside workshop, 30 June 2012.

Chaetostomella cylindrica, a very small pale picture-winged fly (family Tephritidae). Breeding in the heads of various thistles, and especially knapweed, this is a fairly widespread fly, occuring through most of Britain and Ireland, it is nevertheless not common, and I don’t come across it every day. Two specimens were collected during the Ladywell Fields workshop, 13.x.2012.

Cordylura albipes Fallén, a small black and white dung fly (family Scathophagidae). Much more secretive than the common yellow dungfly, Scathophaga stercoraria, and more rarely seen. No doubt feeding in the plentiful dog dung in Ladywell Fields, where it was found 13.x.2012.

Icterica westermanni (Meigen), a small orange picture-winged fly (family Tephritidae). This nationally scarce fly is known from an area south-east of a line from The Wash, to Gloucester to Weymouth. It breeds in the heads of ragwort, Senecio species. Despite its widespread and common foodplant it remains very elusive. This was one of the rare insect species highlighted by Buglife when it challenged proposed legislation to make ragwort a notifiable noxious weed. One was found by general sweeping at the Devonshire Road workshop, 29 July 2012.

Olibrus flavicornis (Sturm), a minute black flower beetle (family Phalacridae). According to the beetle review (1992), this beetle was considered to have red data book status ‘K’ — rare but insufficiently known. It can only be distinguished from others in the genus by microscopic examination of the microsculpture of the wing-cases. At the time it had not been seen since it was recorded in 1950 from Camber on the East Sussex coast. However, it is now known to occur, often in large numbers, on brownfield sites in London and the Thames Estuary. It is still very confined, geographically, and unknown away from this narrow region. It is usually found on autumn hawkbit Leontodon autumnalis, and possibly other similar plants. The larvae are thought to develop in the flower heads, while the adults feed on pollen. Several were found at the Deptford Creekside workshop, 30 June 2012.

Omalus aeneus (Fabricius), a very small metalic blue and green cuckoo wasp (family Chrysididae). One of the rubytails, so called because many are brilliantly red coloured, but not this one. Rubytails are cleptoparasitoids, or cuckoo wasps, laying their eggs in the nests of other wasp species; the hatching grub then devours the host egg and the food stores laid in for it. This one is known to parasitize various common species, but it is very local itself; it is more or less restricted to Kent, Surrey, Hampshire and Devon. One specimen was found during the Devonshire Road workshop, 29.vii.2012.

Pantilius tunicatus (Linnaeus), a large reddish brown and green capsid bug (family Miridae). Found on hazel, birch and alder, this handsome and distinctive bug is fairly widespread in southern England, but not common. Several were found in Sue Godfrey Nature Park, during the Deptford Crossfields Bioblitz, 15.ix.2012.

Rhyzobius chrysomeloides (Herbst), a minute black and pink ladybird (family Coccinellidae). This tiny beetle is extremely similar to a very common species, R. litura (Fabricius), and its occurrence in Britain was only recognized in 2000 when it was found in several Surrey localities. It is probable that this is a recent arrival in Britain and its spread has so far been monitored in Surrey, Kent, Middlesex, Berkshire, Hampshire and Sussex. One was beaten from some hawthorn hedging at the Ladywell Fields workshop, 13.x.2012.

Stictopleurus punctatonervosus (Goeze), a medium-sized brown leaf bug, family Rhopalidae. At the time of the national review of British Hemiptera, in 1992, this species was regarded as being extinct in Britain. It had been recorded from only two localities here, the last in 1870. It has now successfully recolonized Britain since it was recorded in Essex in 1997 and has now become a species typical of the dry, well-drained and sparsely vegetated brownfield sites in and around urban London, Thames Estuary and beyond. Specimens were found at the Deptford Crossfields bioblitz, 15.ix.2012 and at the Ladywell Fields workshop, 13.x.2012.

Not a bad start.

You must be logged in to post a comment.