See what I did there?

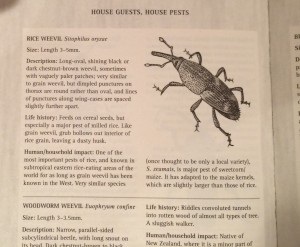

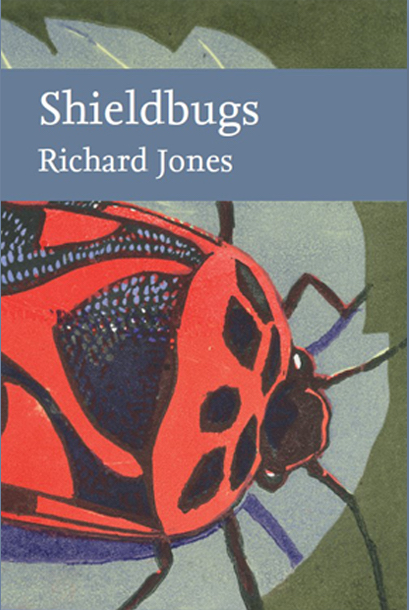

Not only is it the time of year for flying ant days, the last week in July was also my final submission of the typescript for Ants, in the Bloomsbury British Wildlife Collection that I have spent the last two years writing, on and off. The final rejig was a reshuffling of the chapters and renumbering of the illustrations.

I started in July 2018, and half way into the first chapter, I was already writing about those familiar flying ant days. “These mass aerial releases of new males and queens, usually of the ubiquitous black pavement ant, Lasius niger, fill the air with countless millions of flying insects. The flying ant morsels are manna to the swifts, swallows and martins that scream after them, but a potential breathing or blinking hazard for cyclists, and a real visibility nuisance to motorists running low on screen-wash.” And how’s this for a strange coincidence? On the day that I wrote that paragraph, 4 July 2018, it was also flying ant day in Nunhead, where I was writing, and East Dulwich, to which I cycled home in the afternoon. I didn’t swallow any ants on my way, but plenty bashed into my face and got tangled in my eyebrows. It’s a gentle traffic-free cycle ride through Peckham Rye Park, so there wasn’t too much chance of me being dangerously distracted in front of a speeding juggernaut.

However, later that same day the number 2 women’s tennis seed Caroline Wozniacki lost to relative outsider Ekaterina Makarova; magnanimously Wozniacki did not blame the flying ants for her surprise defeat, but earlier she had asked the umpire if anything could be done about the ‘bugs’, and the media coverage was full of images of her swatting at the hordes of winged ants sweeping across Court Number 1 at Wimbledon. There was another media circus event in July 2019 when clouds of flying ants confused the meteorological office by appearing on the increasing sensitive radar as ‘rain clouds’ over Brighton, Bournemouth and Winchester. It was repeated again last month too.

It’s not just that there are more flying ants, it’s also that the radar is becoming more sensitive. In 2020 we had our first flying ant day in East Dulwich in mid-July, but I came across another in Catford on 29 July. Yes, it’s a myth that there is one all-over national flying ant day in the year. There is some local synchronization, but different regions have their own days, and on every warm day between July and September there is a flying ant event going on somewhere in Britain.

That’s Lillian’s shadow, she thought my interest in the pavement looked funny. She was right, but if you look really close you can just make out the queen that I’m interested in.

The book is scheduled for publication in spring 2021 — just in time to pre-empt flying ant media madness next year perhaps.

You must be logged in to post a comment.