There are some events significant well beyond the moment of the actual encounter. They become seminal memories, key turning points in a life, or major influences on future choices. For me, many of these moments appear to involve finding a particular insect. Or in this case a crustacean.

Aged 11, I started at Newhaven Tideway Comprehensive School. It was right on the other side of the town, a good 2 miles walk away; there were various possible routes, but to start with I took the Drove Road into town, then along the West Quay Road, and finally up Gibbon Road to the school. Things have changed a lot since — at that time there was a bustling harbour with a good dozen or so large wooden jetties along this side of the River Ouse, each with several fishing trawlers moored. There was also a large quay area with scoop-cranes to unload gravel and sand from cargo ships. It wasn’t the most direct way to school, and usually took me nearly an hour, but it was the most interesting.

When the tide was out, the muddy and rocky river bank was exposed, and dawdling home I would often go right down to the water’s edge to skim stones or turn over rocks looking for small shore crabs. It was on one such slippery exploration that I hauled over a slimy algae-covered boulder to reveal a biological marvel — the biggest woodlouse I had ever seen. It seemed as big as an egg when it first scuttled off. It was certainly very large, probably the maximum 30 mm that this fantastic creature can reach.

I had never seen anything like it, and knew I had to show it to someone, or they would never believe me. Armed only with a battered briefcase full of exercise books I had nothing to contain my treasure. I was not to be daunted. I walked the rest of the way home with the beast trapped in my cupped hands.

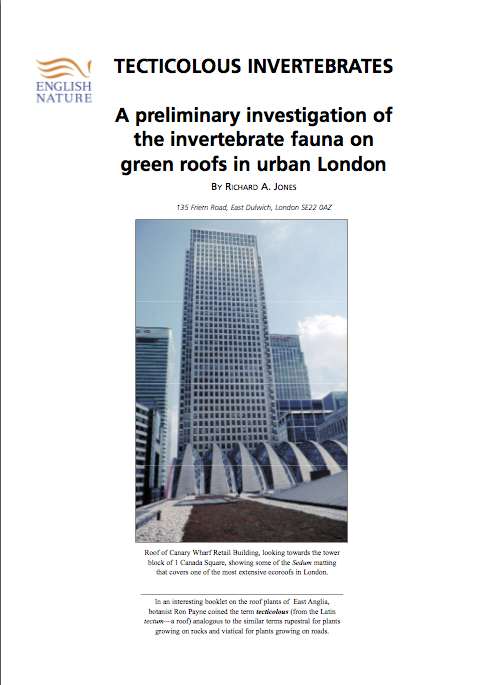

I was slightly deflated to learn that the sea slater, Ligia oceanica, was a widespread and common sea critter, but nothing could take away from me that initial sense of wonder. I still get a thrill when I find one now, under a stone by a rock pool or on the saltmarshes of the Thames Estuary. I was most pleased to find them crawling up the rotten wooden fenders deep in Deptford Creek (where this photo was taken in May 1998) and at the outfall of the River Wandle at Wandsworth, I think the UK’s most inland record.

But despite my childish over-exageration, in the intervening 40 odd years, I still don’t think I’ve ever seen one quite as big as that first.

You must be logged in to post a comment.